Liberal Arts and the Lost Learning of Tools

How Christian liberal arts can help us find our way in a technological age

Words: Martyn Wendell Jones ’10

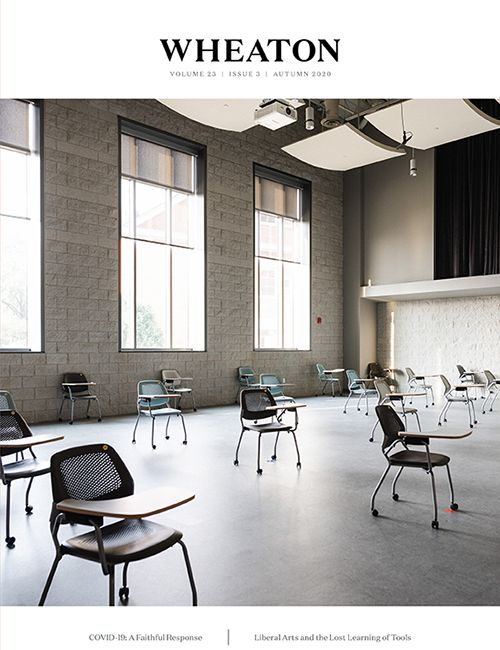

Photos: Tony Hughes

During an economic downturn, it can seem difficult to make the case for the intrinsic value of a liberal arts education. Anyone who questions such an education is likely thinking in consequentialist, “cash-value” terms: Why study topics like history or philosophy when you can learn to code?

Technology presents the American imagination today with a sturdy escape rope from unemployment. If so many college dropouts can become billionaires by being good with computers, then certainly our children could consider poverty-proofing themselves by learning to do the same. If you want to study other things, too—well, isn’t there an app for that?

However, a Christian liberal arts education provides something even more valuable than preparation for a specific job, and that something must be plotted outside the “cash-value” grid. By integrating technology within their disciplines, Wheaton students are preparing not only for future careers in a technologically advanced society but also for a life of meaning and agency in that society.

GRAPPLING WITH FORM AND CONTENT

Technological development moves relentlessly for greater efficiencies, removing the amount of effort required to perform an action. The sort of learning that takes place at Wheaton, however, borrows not from the technologist’s family of metaphors (of progress and convenience), but— often—from the athlete’s: Students try to “keep up with” their professors, “wrestle” with concepts and ideas, and “grapple” with difficult texts. A bit of resistance—and in many cases, a lot of inefficiency—can be essential to true understanding.

Wheaton students are preparing not only for future careers in a technologically advanced society but also for a life of meaning and agency in that society.

But, how do you make appropriate space for the intellectual “workout” of deep learning? This is the kind of question asked by Dr. Steven Park ’85, M.A. ’87, Wheaton’s Director of Academic and Scholarly Technology—and, coincidentally, a maritime historian.

Part of Park’s work is instructional support, helping professors better engage their students in the classroom using iPads or the College’s learning management system— a key resource Park’s office provides the College. The system was instrumental in enabling a smooth transition to online instruction at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Park also encourages faculty to innovate in their own classes using technology.

In his role as director, he helps to award Wheaton’s Academic Technology Grant, which makes up to $30,000 available each year to the winning faculty member on the basis of a creative proposal for incorporating technology into the classroom—“doing things we’re not already doing,” Park said.

A virtual reality headset.

Associate Professor of English James Beitler ’02, M.A. ’04 and Associate Professor of English Richard Gibson were the recipients of the Academic Technology Grant for 2019-20. Beitler used the funds to support a unique module in his Christianity and Fantasy class. Partnering with Arcade V, a virtual reality (VR) lab located just off campus, Beitler assigned students to log three to six hours exploring at least two VR experiences, which they then analyzed in terms of how the VR story positions and persuades the user.

Beitler’s approach to literature and communication emphasizes rhetorical elements, considering questions of genre, formal differences between media- and text-based genres, and the way in which texts “position” the reader: “Who are they asking us to be, and to become? What character am I being asked to inhabit?” he said.

The formal character of media used to convey a given message is often designed to disappear into the content, but Beitler invokes the mantra of famous media theorist Marshall McLuhan to emphasize how to understand media. “I think the notion that ‘the medium is the message’ is foundational. The forms we use are connected to the content, and that is true whether you’re talking about what’s happening on a screen or on the page,” Beitler said. “I try to help my students think about that relationship between form and content in all my classes, about how what we say is so dependent on how it’s conveyed.”

Students in Beitler’s class found the VR experience eye-opening—and disarming. “Virtual reality is completely unlike anything I have ever done,” Rachel Hand ’20 said. Though the Wheaton Improv performer is no stranger to inhabiting roles, the totalizing experience of VR caught her off guard. “The level of embodiment and emotional investment you get in VR is something I have never gotten from a book, a movie, or acting . . . you’re experiencing the story as you.”

For Hannah Bowman ’21, the intellectual significance of VR lay in the way it pushed her “to think more specifically about how to criticize it.” She found herself “adjusting [her] critical mechanisms” and reconsidering her ideas about the nature of criticism in order to better understand how to analyze and assess her experience.

The form and presentation of a VR story can sometimes give it the character of a “technotext”—defined as a literary work that brings its own material embodiment into focus as an essential part of its imaginative world—as in a poem made by cutting out most of the text on a page from a novel, leaving a handful of words scattered between the holes. This creates “traffic” between the physical object or medium of expression and its textual content, Beitler’s English department colleague and fellow grant recipient Gibson said.

Dr. Gibson and art professor Jeremy Botts co-teach a course dedicated to the study and exploration of technotexts. Their syllabus is, in part, a capsule history of the technology of reading itself: it begins by considering the relationship between word and voice to different forms of “the book,” and concludes with a unit on digital technologies. In Gibson and Botts’s course, students come to realize that every text can to some degree be considered a “technotext,” because even a medium designed to “get out of the way” of its content exerts a definitive influence on that content—not just unusually made books or immersive virtual reality experiences.

Two cuneiform tablets.

At each step in the course, students don’t only study the nature of these media, but they themselves become makers, taking up techniques from cuneiform imprinting in clay to letterpress printing to sophisticated multimedia digital storytelling. One of the overarching purposes of the course is to explore the qualities of language, writing, and communication that students normally take for granted, making what is normally invisible visible to them. Botts, the son of a calligrapher, helps students begin to see the invisible side of communication—revealing the “technotextual” element present in all texts—by guiding them through exercises involving letter-forming with a variety of tools.

“Students remember it!” he said, and through their own processes of creation come to recognize the origin of the shapes and forms of letters in the tools used to make them. Botts helps to gently channel creativity with guiding questions: “What’s the transformational potential of any material around you? Could it be holy?” he asked. Because so many key technological advances that Botts and Gibson teach about in the course came through the propagation of Scripture, the sacred potential of materials is often at play in the students’ practical exercises as well.

A letterpress chase with movable type.

Technotexts serve the heuristic function of helping students to realize how much they take for granted—and don’t even see—in their experiences of technologically mediated life. Professor of Communication Read Schuchardt helps his students to unlock this invisible dimension by framing media and technology in terms of environments and ecology. Schuchardt describes his highly interdisciplinary field as “the study of technology’s unintended consequences,” which involves “a consideration of whether [those consequences] are helpful or harmful to the individual, the community, the society at large, or the world in general.”

While “an engineer can make a better smartphone,” Schuchardt wrote in an email, “a media ecologist would help you understand how the smartphone rewrites the entire perceptual code of the entire planet.” The technological regime of the smartphone promises freedom from toil, but fosters dependence on time- and labor-saving devices, generating new kinds of servitude. These are some of the hidden consequences of rapid advances in communications technologies that Schuchardt helps his students to see—and, in some cases, to thoughtfully and selectively resist.

Though he hopes to open students’ eyes to the stakes of our culture’s technological reframing, Schuchardt’s ultimate counsel is against giving up hope: “In a world where social media and the devices themselves have been weaponized against the user, about the only rebuttal the user can make is to idealize their despair, which seems to comprise a large percentage of social media posts.” But if students instead combine an understanding of the true nature of their situation with the knowledge of the Resurrection, they can “push beyond a sort of curated optimism into actual realistic hope.”

TOOLS AND THEIR USES

To reclaim hope under current technological conditions is to reclaim individual agency. Wheaton’s HoneyRock staff understand that restoring a sense of agency often means renegotiating our relationship with our devices—which in turn may require being apart from them for a while.

Rachael Botting ’14, M.A. ’15, and Charlie Goeke ’08, M.A. ’13, oversee the Wheaton Passage and Vanguard Gap Year programs at HoneyRock, respectively. A technology fast is a key part of both programs, aligning with HoneyRock’s guiding principle as “a place apart.”

“‘A place apart’ is about being a place that is physically, relationally, and personally separated,” Goeke said. The idea is drawn from God’s use of wilderness settings in Scripture to draw people out of their permanent homes in order to change their lives. Today, the principle is virtually shorthand for the camp’s restrictions on the use of technology.

Botting said that in follow-up surveys, Wheaton Passage participants consistently rate HoneyRock’s “technology- free atmosphere” as the most impactful part of the program. Many students “don’t know that there is a better option” than the constant pursuit of the easy pleasures of their phones when they arrive at HoneyRock, Botting said, and part of their job—following Christian cultural commentator and author Andy Crouch—is presenting “a reasonable alternative” to that pattern of life.

Crouch’s work also provides a distinction between tools and devices, which HoneyRock staffers find useful as a way to spur student reflection. Where tools serve a specific functional purpose, “devices take away work, and do things for you,” he said, “[they] make things easier.”

By contrast, tools—and “instruments,” as Crouch will describe devices that have been brought back under our control—are one of humankind’s calling cards: from cuneiform and the abacus to Javascript and cloud-based servers, tools are the medium of work. One of the lessons Wheaton students learn through HoneyRock’s “reasonable alternative” and their larger programs of study is to resist the temptations of the ambient, numbing pleasures of their devices, and to see them instead as tools that can be used to specific ends.

Technological tools may require special training and skills in order to be used at all, but the training comes easily to digital natives who know what they need to learn, noted Dee Pierce M.A. ’17, Director of the Center for Vocation and Career (CVC). A Wheaton education positions students to use their resources to fill in their knowledge gaps. Dr. Park’s office makes LinkedIn Learning available to Wheaton students for free, and Pierce recommended a program of self-study through resources such as LinkedIn Learning for students interested in developing the hard skills needed for their desired careers.

However, the most valuable part of Wheaton’s education remains its liberal arts focus, which Pierce said provides a foundation in the aptitudes that will only become more essential the more tech-dependent the global economy becomes. Vocational dexterity, a broadly critical perspective, and the application of a Christian moral framework are all components of a Wheaton College education, which provides students with an inherently creative and flexible approach to their quickly changing fields.

Wheaton’s computer science program provides an example of a highly technical field being taught in a liberal arts context. “Computer science is all about the logic of problem-solving, about the creativity of crafting things with software, and about making tools to improve people’s lives,” professor Thomas VanDrunen wrote in an email. “It is inherently interdisciplinary since every area of study these days has computational aspects.” One example is medicine: VanDrunen wrote that a 2012 CompSci graduate is doing a Ph.D. in computer science focusing on the use of machine learning for medical diagnoses—a project she is undertaking as a break from medical school.

A skeptic of the liberal arts might question the merit of studying other disciplines along with computer science, but VanDrunen’s experience with his students suggests that Wheaton’s CompSci grads are as well prepared for future jobs as any of their future colleagues: all of the CompSci majors in the Class of 2019 reported working in the field within six months of graduation, with two of them employed at Amazon. The foundation in the field of computer science enhanced by building blocks of other disciplines is what enables students “to self-train for a sustained career” instead of narrow training that “becomes obsolete as soon as the technology does.”

Art and communication professor Joonhee Park takes an integrative and holistic approach to his discipline as well, integrating the technicalities of contemporary film production with a foundation in storytelling. Much of his work consists of opening his students’ imaginations beyond the categories that Hollywood has given them. “My definition of a good movie is asking good questions—to leave room [for the audience] to interpret in their own way, and to interpret their own experiences. They can find their own answers,” he said.

Some research programs require narrow technical expertise as well as the ability to ask good questions. Daniel Master, Professor of Archeology, is overseeing an initiative that could fundamentally change his field through the use of cutting-edge technology—and Wheaton students have been directing its implementation.

Dr. Master and students from a variety of majors developed and implemented a novel use for Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) technology to support the Tel Shimron dig.

The project involves the use of a Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) “puck,” which uses light to capture an extremely intricate impression of a surface with millions of points of data. LiDAR has been used in archeological settings in the past—for instance, to map jungle ruins obscured by thick vegetation—but Master’s work at a biblical dig site called Tel Shimron provides the perfect context for developing a novel use of the tool.

Master collaborated with Wheaton’s engineering department to determine if successive LiDAR scans of the Tel Shimron dig from one day to another could be layered on top of one another, making it possible to subtract a later day’s three-dimensional impression of the site from an earlier day’s impression. This would provide “an extremely accurate, rich picture of what it is we actually did” at the site each day.

Much of the technical work on the LiDAR project so far has been performed by Wheaton students from several majors, who were tasked with developing from the ground up every hardware and software system that would enable the LiDAR device to be used. Importantly, there was no existing user base or community to consult for guidance. “We didn’t have any experience to draw on except a user manual, a LiDAR sensor, and the internet,” Rachel Barron ’21 wrote in an email. After working as team manager during the 2018-19 academic year, the physics major took the lead on the project for 2019-20 with a team of both students and faculty. With fellow student McKenzie Blank ’21, she also directed the first stage of implementation on-site at Tel Shimron during the summer of 2019.

During that summer, Barron focused on developing an algorithm “to return the differences between [the] dense point clouds” of two successive LiDAR scans. This past academic year, the team has prioritized developing the ability to track the movement of the sensor during its scans, which could increase the accuracy of surface data.

Barron describes her physics background as valuable for the problem-solving she has been required to do, but notes that her exposure to other disciplines through her Wheaton classes is what made it possible to bring her training into productive dialogue and engagement with her collaborators. She wrote, “There really is no way to talk about what I learned from this technical project and not touch a liberal arts influence.” Interdisciplinary collaboration has been essential, with researchers from physics, engineering, computer science, archaeology, and geology working together, each with a different way of understanding problems and determining approaches. In the summer of 2019, for example, Barron prioritized implementing an inertial measurement unit to improve the accuracy of their LiDAR data, but Blank, her colleague with an engineering background, advocated for using reference points that could be found in the data after collection instead. In the end, the team collaborated on both approaches to improve the accuracy of their data. She anticipates carrying the skills she has learned while working with LiDAR into cybersecurity, a field to which she felt called during her work on the project—a virtuosic pivot from one technically demanding field to another, as her education has prepared her to do.

In some ways, Barron’s work with LiDAR represents an apex liberal arts experience: It requires a working knowledge of numerous fields and methodologies, technical sophistication, and robust “success skills”—such as knowing how to write a clear paragraph or knowing how to ask good questions in a conversation. Such skills are a particular strength of Wheaton alumni.

Perhaps the closest we can come to identifying the value of a Christian liberal arts education beyond its “cash value” is to highlight Barron’s sense of her own goals, skills, and future: An intensely challenging project led her to develop technical abilities she can use in a field that she has not specifically prepared for, but feels ready to pursue. It is important to train people for future jobs, and for Christian liberal arts institutions in a time of increasing technological dependence, it is important to produce people who make their own way with a variety of tools—in short, to produce people who are free.