55 Years of the Faculty Faith and Learning Seminar

Commemorating Wheaton College’s Historical Commitment to Academic and Spiritual Excellence

Words: Liuan Huska ’09

Photos: Kayla Smith

Overhead view of the main stairwell in Blanchard Hall.

Photo by Kayla Smith.

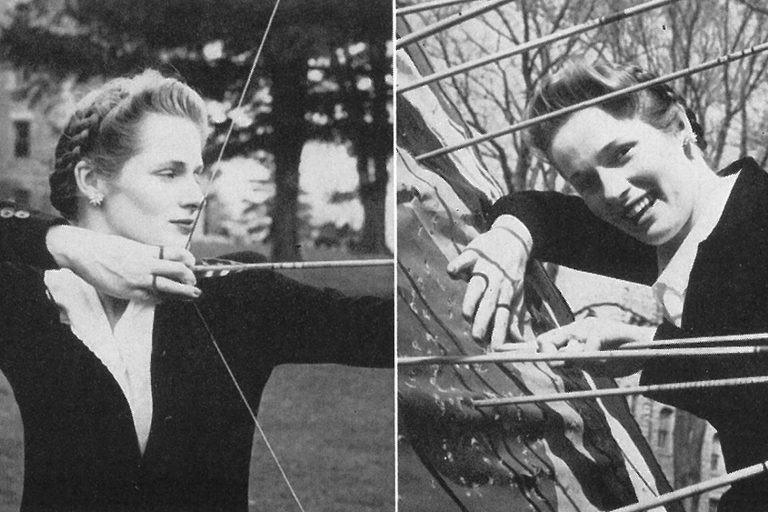

Monday, July 21, 1969. While the world was abuzz with watching the first human walk on the moon just hours earlier, another momentous endeavor launched in a Fischer Hall meeting room. Nine faculty members, from soccer coach Joseph Bean to art professor Miriam Hunter, gathered to put their faith in conversation with their respective disciplines. There was, in the words of participant and Professor of English Emeritus Dr. Leland Ryken HON, “an awe-inspiring sense of the tremendous importance of what we were doing.” The month-long seminar kicked off 55 years of the Faculty Faith and Learning Seminar, which continues to define Wheaton’s identity to this day.

Today, all tenure-track junior faculty receive a course release in their second year to join a cohort of professors across disciplines in a yearlong seminar integrating their field of study with a biblical understanding of God’s world. To qualify for tenure, each professor must submit a paper or project that articulates a Christ-centered approach to their field. “Simply put, the integration of faith and learning means ‘thinking Christianly’ about everything,” writes President Philip Ryken ’88 in a chapter from the forthcoming volume Habits of Hope: Seven Educational Practices for a Weary World (IVP, 2024).

The faith and learning framework is now baked into all aspects of the College, from hiring practices to professor evaluations to the Christ at the Core curriculum. It informs how professors teach and how students and faculty members engage across disciplines. Wheaton has become a model for how to integrate faith and learning well for other Christian colleges and universities.

“It’s not too strong to say that it’s a key reason why Wheaton exists,” said Dr. Timothy Larsen ’89, M.A. ’90, current director of the Faith and Learning Program. “It is very difficult and rare and precious to bring together experts who also really believe the gospel and are really committed to being faithful to Jesus Christ to mentor, disciple, and form students so they can be whole persons in their disciplines.”

EARLY INFLUENCERS OF FAITH AND LEARNING AT WHEATON

When Dr. Carl F. H. Henry ’38, M.A. ’41, started his undergraduate career at Wheaton, a new evangelicalism was gaining momentum in response to the fundamentalism pervading the 1920s and ’30s, which saw everything intellectual as a threat to biblical faith. Henry’s work, including the 1946 book Remaking the Modern Mind (Eerdmans), became foundational reading for others who shaped the faith and learning conversation, including former seminar director Dr. Arthur Holmes ’50, M.A. ’52, and Dr. Mark Noll ’68, who mentored many Wheaton faculty at this intersection.

Henry’s mentor, Frank Gaebelein HON, became the first director of Wheaton’s Faith and Learning Seminar, which President Hudson Armerding initiated in 1969. Gaebelein was headmaster of the Christian college-preparatory Stony Brook School on Long Island in New York. He co-edited Christianity Today with Henry in the 1960s and wrote The Pattern of God’s Truth: Problems of Integration in Christian Education (Oxford University, 1954). Greg Morrison ’87, Associate Professor of Library Science, documented this early history in an online library guide that came out of his own faculty faith and learning project.

During that 1969 summer seminar, Gaebelein brought in leading Christian thinkers, such as Clark H. Pinnock and Calvin Seerveld. He also assigned readings like The God Who is There by Francis Schaeffer (IVP, 1968) and Christian Letters to a Post-Christian World by Dorothy Sayers (Eerdmans, 1969). Faculty met for lectures and discussion during the day and spent afternoons researching and writing their own faith and learning papers.

For Leland Ryken, the seminar forced him to “put it all together” in regard to faith and learning. “I took the assignment of my paper very seriously, and it laid the lifelong foundation of my philosophy and methodology for how to integrate the study of literature with the Christian faith,” Ryken said. Ryken’s 65 books, including How to Read the Bible as Literature (Zondervan, 1984), represent applications of the principles he codified in his original paper.

FAITH AND LEARNING EXPANDS AT WHEATON AND BEYOND

Holmes took over the Faculty Faith and Learning Seminar in 1974, directing the program for nearly two decades while teaching philosophy at Wheaton. His book The Idea of a Christian College (Eerdmans, 1975) has been widely read by members of the Christian College Consortium and later the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities. The title of Holmes’ book All Truth is God’s Truth (Eerdmans, 1977) echoed through classrooms and conversations on campus. The book even made its way into the hands of Provost Emeritus Stanton Jones, who at the time had never heard of Wheaton College. “Where does this guy teach?” Jones wanted to know.

When Jones joined the faculty in 1981, participation in the seminar was advised but not required. Jones himself didn’t participate, having just finished a doctorate program and struggling to keep afloat with finances and workload. However, he was informally mentored by philosophy professor Dr. C. Stephen Evans ’69.

“The more I talked to other faculty, the more I realized the integration of faith and learning was kind of uneven—how deeply committed they were, how they understood it,” said Jones. He thought, “We really need to make something more rigorous.”

Jones got his chance when he became provost in 1996. Jones and a team of others including Holmes, Noll, and Dr. Roger Lundin ’77 raised $2 million for an endowment and $2 million for expanding the Faculty Faith and Learning Seminar into a full-fledged program, which began in 1997. Key to the new program was a reduced course load for faculty to participate in the yearlong seminar during their second teaching year.

“I’m super grateful that Wheaton found funding for this,” said Larsen, who also serves as Carolyn and Fred McManis Professor of Christian Thought and Professor of History. “I see that as a stress point for so many colleges, where there is the temptation to add more unpaid duties to their faculty.” The institutional financial backing allows faculty to take time to truly integrate biblical beliefs with their studies, said Larsen, which speaks volumes about Wheaton’s priorities. Quoting Luke 12:34 (NIV), he added, “For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.”

Jones and his team designed a yearlong seminar curriculum piecing together what they deemed the best resources available, though nothing was exactly like what they had in mind. “You always understand the world through a grid of belief,” Jones said. “Sometimes those beliefs get pushed and shaped, but you organize the world differently depending on how you look at it.” For Jones, integrating faith and learning at Wheaton is about how our fundamental grid needs to be shaped by Christian beliefs.

Jones frequently shared the seminar curriculum with other Christian colleges and universities, which Larsen continues to do today. “It was really a delight to see the Wheaton model spreading and morphing in other schools,” Jones said.

A TWO-WAY DIALOGUE

Dr. Kristen Page, Ruth Kraft Strohschein Distinguished Chair and Professor of Biology, said she arrived at Wheaton in 2000 with very little understanding of faith and learning integration. Trained at Purdue University, a public land-grant school, she knew how to ask questions and design research as a biologist. During the Faith and Learning Seminar, in a cohort with many new Bible and theology professors, she understood that everything she did had to be “flavored” by her faith but wondered, “How does a scientist do this?”

“I was clueless when I came to Wheaton,” Page said. During the interview process, however, she was drawn to the campus because of the students. “They were just so genuine, curious, smart, and asked really good questions.” Although she couldn’t articulate it then, this quality that pervaded campus had to do with Wheaton’s faith and learning commitment. “The reason for their curiosity was their faith,” Page said.

Through the seminar and her subsequent faith and learning paper, Page realized that though her commitment to Christ wouldn’t change her research methods, it did drive what questions she asked. “I’m a disease ecologist because I really, really care about the intersection of how we treat God’s creation and how it often causes our neighbors to suffer,” Page said. Her faith and learning paper used case studies that connected ecosystem degradation with disease spread, arguing that we perpetuate the suffering of our neighbors when we perpetuate the suffering of creation.

Page’s paper became courses she now teaches—Global Health and Ecosystem Health. It was also the foundation for her Hansen Lectureship series, “Creation’s Call: Stewardship Lessons from Middle-earth and Narnia,” later published as The Wonders of Creation (IVP, 2022). The book discusses how spending time in fictional landscapes can expand our propensity to love the natural world. Exploring ecology through a faith lens is an ongoing journey for Page. “I still have lots of room to grow,” she said.

While the Faculty Faith and Learning Program helped Page integrate Christian faith with her discipline, faculty in the Department of Biblical and Theological Studies are pushed to integrate in the opposite direction, adding the perspectives of other disciplines to their studies.

Associate Professor of Theology and Urban Studies Dr. Gregory Lee started teaching theology at Wheaton in 2011 as an Augustine scholar. For his faith and learning project, he chose to explore how Augustine’s understanding of sin speaks to questions of individual and collective responsibility related to mass incarceration, which disproportionately affects black men and other minority groups.

“I never really thought of myself as being involved in scholarship on race or ethics in general,” Lee said. “There’s no way I would have written on this topic if it weren’t for the faith and learning paper requirement.” Lee’s paper was later published in the prestigious Journal of Religion. He now works at the intersection of early Christian studies, Augustine, and race and urban issues.

Lee credits his growth as a scholar and educator to Wheaton’s emphasis on the integration of faith and learning. “Every faculty person outside my field is required to engage with Bible and theology,” he said. “All these faculty are available for me to draw on as a theologian to think in an integrated way about social issues on the ground. This has made my theology much less abstract and theoretical—more tethered to grassroots concerns of actual communities.”

This two-way dialogue was Jones’ hope all along. “It’s not a one-way street,” he said. “I look at research through the grid of faith, but I also have that feedback challenge my interpretation of Scripture. The dialogic process is really important.”

THE FUTURE OF FAITH AND LEARNING

Wheaton’s Faculty Faith and Learning Program has grown and changed with new faculty and directors. Dr. Gary Larson M.A. ’83 led the seminar when it became a requirement for tenure-track faculty, followed by Jacobs and Lundin.

Jacobs, currently the chair of Christian Thought at Baylor University, started teaching English at Wheaton in 1984 with very little theological education. His own experience with faith and learning as a junior faculty member was piecemeal: The seminar then was a one-week summer event with Holmes. Jacobs wasn’t prepared for the questions students would ask, so he often sought help from senior faculty like Dr. Robert Webber, Lundin, and Noll.

“If you’re a young faculty member, it relieves you of the pressure of having to find and approach colleagues,” said Jacobs, describing one benefit of the program in its current form. “The theological education comes to you.” When Wheaton began the current one-year format with a course reduction for participating faculty, this was, as far as Jacobs could tell, “something far beyond what any other Christian college did. Few others would have had the commitment to faith and learning integration, and still fewer would have the financial resources.”

While he was director, Jacobs oversaw the first faculty faith and learning project that wasn’t a paper. Professor of Communication Mark Lewis, who also directs the theater program at Wheaton, submitted a video of a live Shakespeare performance supplemented by interviews with theater graduates working professionally, telling a story of how their faith connected with their love of theater. Lewis was worried that his project wouldn’t be considered legitimate compared to the traditional paper, but wanted to convey his synthesis of faith and learning in the medium of his discipline—performance. Lewis’ project was accepted and he received tenure, which he considers a miracle. “For Wheaton to open its mind to the idea that this is actually scholarship felt to me like Wheaton opening the door and saying, ‘You belong here, too,’” Lewis said.

Since then, other faculty have submitted creative faith and learning projects. Professor of Music (Composition, Music Theory) Dr. Shawn Okpebholo composed a flute solo responding to a poem by Associate Professor of English Dr. Miho Nonaka, who was in the same seminar cohort. “On a Poem by Miho Nonaka: Harvard Square” has become one of Okpebholo’s most-performed pieces worldwide. The two colleagues collaborated again when Lundin passed away within days of another English professor, Dr. Brett Foster. Nonaka penned a poem in memory of Lundin, which Okpebholo responded to through a musical composition. Both pieces were presented at a 2015 concert in honor of Lundin and Foster. “That evening was a moment of rising,” Nonaka said. “It expanded our horizon of what could be achieved when different artists come together.”

The seminar was one of Okpebholo’s favorite experiences at Wheaton. “I was talking about core issues with poets, theologians, scientists, psychologists, and economists,” he said. “I’m not just around musicians, and that makes me a better composer.”

Besides the second-year required seminar, Wheaton’s Faculty Faith and Learning Program has supported other advanced and supplemental seminars, such as Noll’s seminar on Christology and scholarship, which led to his book Jesus Christ and the Life of the Mind (Eerdmans, 2013). Lewis led a seminar for faculty using theater exercises to explore the theme of mentorship. “Working with Mark Lewis really was, without exaggeration, a life-changing experience,” said Professor of Anthropology Dr. Brian Howell. “I’m much more aware of the ways my students need connection—with each other, with God, with the material we engage in class—and use theater games as a means of getting them ‘into the room.’”

Larsen emphasizes that the faculty seminars have become less theoretical and more pedagogical over the years. “It’s becoming much more about, ‘How do I embody this? How do I live it out? How do I reflect this in the classroom?’” Larsen said.

As the College has hired more international faculty, the dynamics of the conversation have also changed. “The default was reading a lot of authors who came from similar backgrounds,” Larsen said. But now, faculty are earnestly asking, “What does it mean that Christianity is global? That we’re serving a global church?”

As Wheaton’s Faculty Faith and Learning Program continues, President Ryken sees its importance for this life and beyond. “In some mysterious, beautiful way, the things we learn and experience on earth are integral to our destiny,” he writes in his forthcoming chapter in Habits of Hope, referencing themes from Marilynne Robinson’s novel Gilead. “Christian education will find its grandest fulfillment in the life to come, when our highest hopes for the integration of faith and learning will prove to be eternal.”

.jpg)