Beyond Blanchard

Wheaton Professors Explore Calling in Academia, the Church, and the College’s Global Community

Words: Bethany Peterson Lockett ’20

Photos: Tony Hughes and Kayla Smith

Dr. Mandy Kellums Baraka M.A. ’13, Associate Professor of Counseling, uses play therapy to help children communicate.

Traditionally, large universities emphasize publishing and research output for their faculty, while small liberal arts colleges tend to focus more on the classroom learning experience. Yet since its founding, Wheaton College’s professors have been motivated by their faith to propel their fields forward within and beyond the classroom doors.

BRINGING A HISTORY OF SUCCESS TO WHEATON COLLEGE

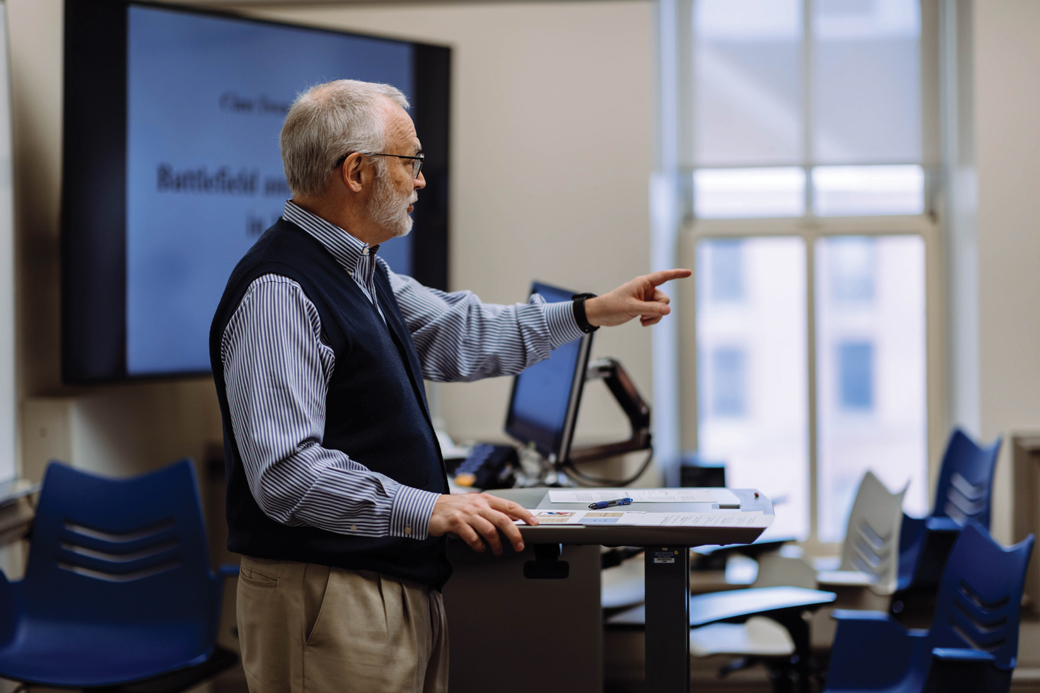

Professor of History Dr. Tracy McKenzie had his dream job. As a tenured professor for the University of Washington’s highly respected history department, he was writing books and articles while serving as an endowed chair. But he began to feel a pull toward something different.

Dr. Tracy McKenzie teaches a 300-level class on the American Civil War.

“I actually began to feel considerably unfulfilled,” McKenzie said. “Over time, I felt more and more of a desire, a sense of calling, to produce scholarship for the church.” And not only for the Christian leaders, pastors, and scholars, but also for the “folks in the pews.”

In the 14 years since McKenzie accepted a position at Wheaton, where he holds the Arthur F. Holmes Chair of Faith and Learning, he’s lost none of his commitment to great research and scholarship. But he’s gained the ability to explore with students and colleagues “what it means to bring Christian values like love and humility into the way we engage the subject.”

“Every day that I’m teaching, I feel like I’m also sharpening my own understanding of my calling,” said McKenzie. “I don’t have to live a divided life. I get to bring all of me into the classroom and my relationships with students every day, and that’s not something I take for granted at all.”

BUILDING UNITY

Due to Wheaton’s position as a nondenominational Christian liberal arts college, its academic faculty hail from various backgrounds, countries, and disciplines. Many professors find the variety of Christian faith to be an opportunity to overcome traditional divisions and speak to the unity of the global church.

This work may be especially relevant for what Dr. John Dickson calls “post-Christian America.” As an Australian citizen, Dickson has lived and worked his entire career in a post-Christian environment where populations are statistically less likely to have a religious affiliation. He loves to explore how we can reach these places “thoughtfully, generously, yet with conviction and truth.”

Dr. John Dickson recording an episode of the “Undeceptions” podcast.

After more than two decades of teaching at large, public universities in Sydney, Australia, he can now combine his careers as a musician, historian, pastor, and documentarian into one role as the Wheaton College Graduate School’s Jean Kvamme Distinguished Professor of Biblical Studies and Public Christianity.

“It’s a joy that the job here at Wheaton doesn’t limit me to doing one thing,” he said.

In most larger universities, specializing is expected, but a Christian liberal arts environment allows for increased integration and cross-disciplinary research, especially when it comes to faculty exploring their faith in their work. Dickson currently combines his multiple disciplines into one unique project: resurrecting the world’s oldest known hymn. Collaborating with two Christian artists—Ben Fielding and Chris Tomlin—Dickson is producing a documentary on a fragment of an ancient Christian hymn that was discovered in Egypt and transforming the music into a modern praise and worship song for today’s churches.

Beyond the ancient song’s musical value, Dickson sees the hymn’s renewal as a historical contribution. “The song predates all modern denominations, so this represents a kind of fundamental unity,” Dickson said. Years before the Council of Nicaea established basic Christian doctrine, this ancient hymn “praised the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. That’s what makes it so relevant to our modern church—our belief in the Father, Son, and Spirit, the giver of all good gifts.”

Dickson also hosts the Undeceptions podcast, exploring questions about religious beliefs with an atypical audience: He speaks directly to nonbelievers.

“I just think it’s possible to present classical Christian ideas in a way that leaves people thinking, ‘Even though I don’t agree with you Christians, you’re not as dumb or mean as I thought,’” Dickson said. “And hopefully, the podcast leaves people wanting to have a second look at the Christian faith.”

Dr. Misook Kim in the Armerding Recital Hall.

Guest Lecturer (Composition, Music Theory) Dr. Misook Kim, a professional composer alongside her teaching commitments, also explores divisions and unity through unexpected channels.

When we think of an opera, imagining lavish stages, elegant clothing, and the Italian language is simple. However, one may not picture an airport waiting room, customs officers, and a combination of English, Spanish, and Korean. The latter are all features of Kim’s operatic scene, which is part of a grant-funded project supported by the University of the Incarnate in San Antonio, Texas.

Kim, who has taught at Wheaton since 2006, envisioned the scene as a celebration of “the beauty of diversity, culturally and artistically.” As a composer from South Korea, she has witnessed divisions in the global church, including political and linguistic barriers. Her operatic collaboration with extensively published poet and Wheaton College Provost Karen An-hwei Lee shares the frustration of people who cannot communicate but “are trying to use one language, which is that of the children of God with the grace of God.”

Kim sees musical education as a path toward unity for the global church because she believes it can break down walls like nothing else.

“Music is a very powerful force,” Kim said. “It is a great source for communicating with each other whether we understand the language or not. Sometimes it does not matter, because music touches our hearts.”

REDEFINING SCHOLARSHIP

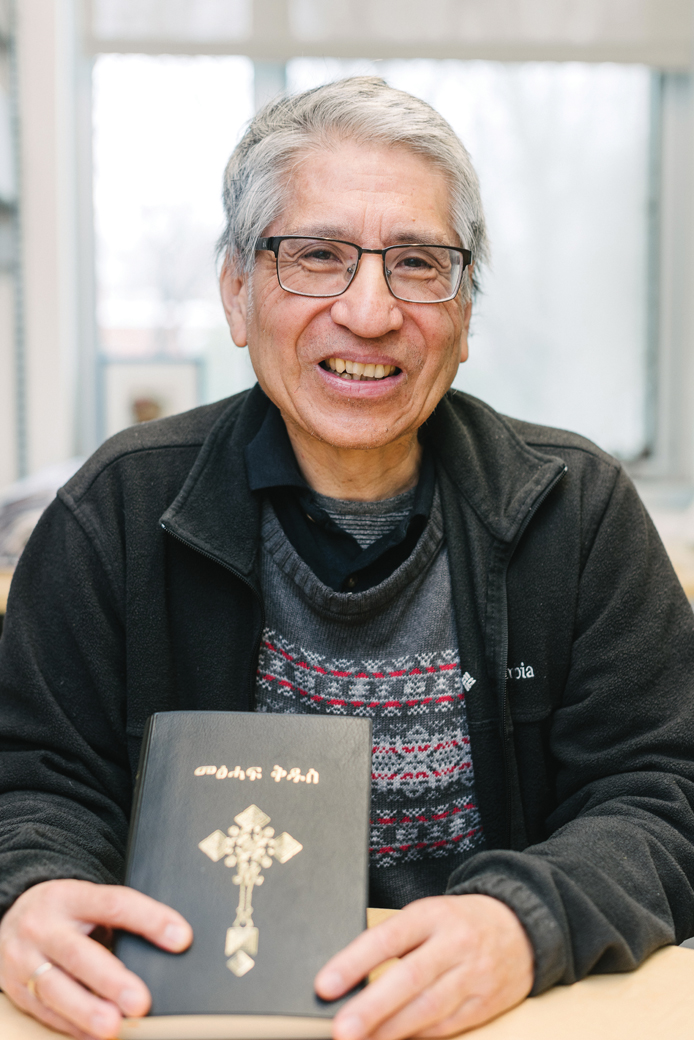

Professor of Mathematics Dr. Paul Isihara is retiring from Wheaton after 37 years. One would never guess that in his first year of college, he gave up on mathematics and dropped out.

Dr. Paul Isihara with a copy of the Tigrinya Bible, translation work that was supported by the Timothy Project.

As the son of a leading physicist, Isihara once believed that the only path to success was to study a discipline at its highest level, chasing award-winning research and academic acclaim. But as a first-semester college student at Princeton University, he was unprepared for the rigor of his highly abstract math classes. Although he dropped out the next semester, he had become a Christian and experienced the joy of serving with an inner-city ministry in Buffalo, New York. He eventually found a new calling to connect his talent for mathematics and his passion for ministry.

“Every academic discipline is worthwhile for a Christian to pursue, and there are ways to directly or indirectly integrate those with our faith, including math,” Isihara said. “But for me, the idea of math being used for humanitarian purposes is one explicit way to connect the two.”

At Wheaton, Isihara dedicated his math research to mission and society, even teaching a popular course on that same topic. He worked with the Wheaton in Chicago program by providing data support for violence reduction and housing equity programs. He also serves as chair of the board for the Timothy Project, a nonprofit organization founded by Wheaton coach Don “Bubba” Church ’57 in 1985. In this role, Isihara uses data to identify the greatest needs of internationally displaced persons (IDP) from the civil war in Tigray, Ethiopia, and shares creative problem-solving ideas with aid organizations.

“We don’t have to be doing what other mathematicians in the world are doing,” Isihara said. “God could have given us something a little different to do.”

Dr. Mandy Kellums Baraka M.A. ’13 in her office.

The value of blending disciplines is also true for Dr. Mandy Kellums Baraka M.A. ’13, Associate Professor of Counseling, who recently earned her credential as a registered play therapist. Play therapy is a research-informed, developmentally sensitive modality that focuses on helping children communicate with others and heal in spaces that feel comfortable to them (as opposed to talk therapy with adults).

“We know that children aren’t going to enter counseling using words in the same way that adults are,” Baraka said. “As we think about the therapeutic process of play, it gives access to children using toys as their words and play as the language of communication.”

Since Baraka started teaching at Wheaton in 2021, she’s continued to serve the City of Chicago by seeing clients in a clinical practice once a week. Her practical knowledge and access to new insights in the field also benefit her students as they launch their own clinical careers.

Associate Professor of Music (Musicology) Dr. Johann Buis is another Wheaton faculty member expanding how and why research is conducted in his field. Like many music history scholars, Buis began his career by studying early European music from the Renaissance and Baroque eras. “You had to study Western music to validate yourself,” he said. Then he discovered ethnomusicology, a form of cultural anthropology that asks questions about music and society. “European musical research had a long tradition—and with many, many, many scholars—but the music of the African people was in need of a lot of groundbreaking work,” he said. As a South African citizen, “It felt like coming home.”

Buis, who has worked at Wheaton for 20 years, recently traveled to one of the world’s most remote places—rural western Tanzania—as a Fulbright Scholar. Although this region is usually overlooked, it is the epicenter of a previously undocumented form of indigenous music and dance, utilizing a combination of a three-legged stool and clay pot as common kitchen items.

“I call it finding a titanic in Africa,” Buis said. “It was out of sight for so many scholars.” He hopes he can bring visibility and recognition to “what the local people see as part and parcel of their festivities. It is really a phenomenon that is one-of-a-kind in the world.”

Dr. Johann Buis shares an Ethiopian krar (or East African lyre).

CHANGING CULTURE

Dr. Theon Hill teaches a communication class.

While some students graduate from Wheaton to pursue full-time ministry, many embark on what they may view as “secular” professions in the workplace. Paraphrasing 1 Corinthians 10:31, Associate Professor of Communication Dr. Theon Hill explains, “If we take the biblical mandate of ‘whatever we do, do all for the glory of God,’ that means we need a biblical account of how we inhabit the workplace as faithful believers.”

Hill has taught in the communication department at Wheaton since 2014 and serves as the codirector of the Center for Faith and Innovation (CFI). Founded by Dr. Hannah Stolze M.A. ’19, CFI is designed to encourage and support Christian leaders in the marketplace. The team works to develop Wheaton students as the next generation of leaders, but they also reach a broader network of alumni and other Christian executives through workshops, webinars, and conferences.

“Many students have been raised to almost look down on business as being not as missional,” said Hill. “As they come through our program, they realize, ‘Wait a second. God can actually work through me in the world of business in similarly important ways to a pastor or missionary.’ You see this spark of inspiration that God can use their unique gifting to advance the kingdom of God.”

MAKING DISCIPLES

First and foremost, Wheaton professors are educators. The small class sizes make it possible for faculty to have a real investment in their students, both academically and personally. For example, Isihara made it his goal to invite undergraduate students to research projects and even publish papers with him.

“I find it very rewarding to be able to work collaboratively with students,” Isihara said, adding that students often have perspectives and ideas that benefit him greatly. He even involved his capstone class with his IDP work in Ethiopia, putting their learning to the test in a crucial real-life situation.

Similarly, Baraka views her classes as a chance to be co-creators with the undergraduate and graduate students who walk through her door.

“We are so often learning together as a parallel to what occurs in the counseling office,” she said.

At Wheaton, students and professors can also grow in their faith together. Sometimes, the most valuable thing a professor can bring to the classroom is his or her life experience as a Christian. When Associate Professor of Biological and Health Science Dr. Dana Townsend arrived at Wheaton 12 years ago, it was her first time on the faculty of a Christian school. Previously, she taught anatomy and physiology at a large state school for 30 years. The first time her Wheaton science colleagues prayed with her, Townsend wept for joy. On her first day of teaching classes, she wondered aloud how she would adjust to a new school. After the lesson, a third of her class approached her with encouraging words. It was incredible to her to be “part of a community that would teach me, by having a great cloud of witnesses, how to be Christian in my workplace.”

Gradually, Townsend felt that God was working in her to be a witness for her students, too. She chose to be vulnerable to her classes about what God was teaching her and to share about her own journey to strengthen and encourage her students.

After two years at Wheaton, the Chaplain’s Office asked her if she would be willing to share her testimony during Chapel. Townsend prayed, “I’m going to tell them in detail what they’re asking me to say. And they will surely tell me, ‘No, that’s too much.’ And that’s how I’ll know I’m not supposed to do this.” She marched into the office and shared details of her life that few other people knew at the time, expecting rejection. Instead, she received the feedback, “It’s perfect. Just like that.”

She was terrified as she got up to share her testimony when the day came for her Chapel address. But afterward, students and faculty flooded her office hours to share about their own lives and to celebrate what God had done for her. She describes it now as a book in her “faith library” that she goes back to often to remember God’s faithfulness.

McKenzie summed the joy and opportunity of teaching and researching at a Christian liberal arts college by saying, “There is a certain perspective in our society that secular institutions have academic freedom and Christian institutions would be very restrictive. I think that depends on your sense of calling and your values. For me, it’s been just the opposite.”

Dr. Dana Townsend with students in the anatomy lab.